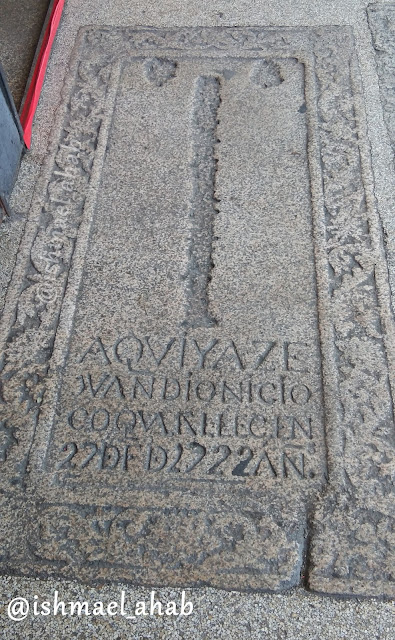

The floor in front of the door of Binondo Church catches my attention every time I enter the church. Of the bland marble stones laid in front of the church, only this big particular part has inscriptions that are difficult to understand.

|

| The mysterious tombstone at the door of Binondo Church. |

The word that I read in the tombstone is AQVIYAZE JVAN DIONICIO. Below those big letters are 22 DED 1722 AÑ.

I suspected that this suspicious marble stone is a tombstone but I couldn't understand the text since I do not know how to read Spanish. So I enlisted the help of Google translate, which was also as clueless as me. At least Google search pointed me to a photo of a tomb of the Spanish king Don Pelayo that also bears the text AQVIYAZE. So, my suspicion was somehow confirmed that Binondo Church's tile is a tombstone.

A change in keywords brought me to an online paper which gave the proper rendering of the text. According to the paper, the text should be read as:

AQUI YAZE

JUAN DIONICIO

COQUA FALLEC EN

27 DE F. DE 1722 AÑ

Super facepalm for me. I forgot that in old writings, the V should be read as U.

The text, when translated to English, read as:

HERE LIES

JUAN DIONICIO

COQUA WHO DIED ON

27 OF FEBRUARY OF 1722

My suspicion is finally confirmed to be correct. That marble stone, or better known as piedra china, at Binondo Church's door marked the grave of Juan Dionicio Coqua, who died on February 27, 1722.

This discovery actually created more questions for me. Who is Juan Dionicio Coqua? And why was his tomb placed at the church’s door where churchgoers will step on it? These questions pushed me to do more online research and to the discovery of another dark part of our country’s history.

The history of Binondo is characterized by the inter-racial tension between the natives of Manila (the so called Indios), the Chinese immigrants, the Chinese mestizos (those who mostly have Chinese father and Indio mother) and the ruling Spaniards. The land of Binondo was donated in 1594 by Governor General Luis Pérez Dasmariñas to the Chinese who converted to Christianity. Some historians say that the donation was a way for the Governor General to skirt the royal decree of expelling the Chinese from Manila, possibly due to their involvement in the attack of Chinese pirate Limahong in 1574. However, based on another source, I believe another reason why the Chinese converts were transferred to Binondo was to separate the "good" Chinese from the "bad" Chinese living in the old Parian, which is located in the now Liwasang Bonifacio and Manila Post Office.

|

| The Chinese or Sangleys as depicted in the Murillo-Velarde-Bagay Map. (Source: Wikimedia) |

1594 is the year of great tension in Manila because of the arrival of a great number of Chinese ships loaded with men and weapons. The Spanish authorities suspected the Chinese but still welcomed their dignitaries. It was believed that the Chinese planned to invade Manila while the Spaniards were on a military campaign in Moluccas. However, they changed their minds when they saw the Spanish armada.

The mandarins thought that the Spanish fleet is on a campaign in the Moluccas. The mandarins' intel was correct but already inaccurate. The military campaign to Moluccas was put into action by Governor General Governor Pérez de Dasmariñas in 1593. The military campaign did not push through, however, because the Chinese crew of the flag ship mutinied and killed the governor general. Had the Moluccas campaign pushed through then the Chinese mandarins may have been successful in invading Manila. Thus, it can be said that the planned invasion of Manila by China in 1593 was foiled by their fellow Chinese who mutinied during the Spanish military campaign to Moluccas.

Luis Pérez Dasmariñas, the son of the governor general killed by mutineers in the aborted Moluccas campaign, is the new governor general. As I said previously, Luis Pérez Dasmariñas is the governor general who made Binondo as the new settlement for the Chinese. In this new Chinatown, the Chinese were heavily taxed and had to pay large amount of fees as well as provide yearly labor to the government.

In May 1603, Chinese Mandarins visited Manila again. There mission is to search for a certain mountain in Cavite that produces great amount of gold and silver. The Spanish was suspicious of the mission but they still welcomed the mandarins like in their previous visit. The mandarins eventually left Manila but the colonial government were wary of the Chinese immigrants in Binondo. The result of this animosity is the so-called Chinese Rebellion of 1603 (according to colonial government sources) or the Chinese Massacre of 1603 (according to Chinese immigrant sources). The casualties of that event included the many dead Chinese immigrants, native Filipinos used as soldiers by the colonial government, and the death of colonial government officials that included Luis Pérez Dasmariñas himself.

|

| Old map of Binondo circa 1739 as seen in the "Topographia de la Ciudad de Manila" by Hipolito Ximenez. (Source: The British Library) |

Despite of the “bad blood”, the colonial government couldn't give up the Chinese immigrants because of their link to the Chinese mainland, which is vital for the success of the Galleon Trade. It is this link that the Dominican friars planned to take advantage of when Binondo was placed under their care 1596. The Dominicans used Binondo as their springboard for their missions to China.

The friars originally built Binondo Church with a cemetery adjoining it. Actually, the cemetery outside the church is for commoners while the prominent persons in the community, especially those who were the church's great benefactors, were buried inside the church. The big tombstone is then a proof that Juan Donicio Coqua was one of the prominent benefactors of Binondo Church.

Little is known about Juan Dionicio Coqua. Internet research did not yield good information. Facebook search yielded little result of any person who is surnamed Coqua. The only clue that I got is that coqua is a Latin word for "cook". Maybe Juan Dionicio Coqua was a cook or a restaurateur in Binondo.

Unfortunately, the prominence of Juan Dionicio Coqua and his family didn't guarantee that his final resting place will not be disturbed. There came a time when the Dominicans turned Binondo Church into a Filipino church. The result is that all piedra china were removed and destroyed. I cannot find any source when this happened but it can be after the British Invasion of Manila. During that incident, many Chinese immigrants sided with the British. Unfortunately, the Seven Years Wars between Spain and Britain ended and the treaty between the two nations declared that Manila will be returned to Spain. The Chinese in Manila received punishment from the Spanish colonial government and many of them were deported back to the mainland. Traces of Chinese culture in Binondo Church were possibly removed during that time.

The piedra china inside the church was defaced. According to the Richard T. Chu the Teresita Ang See, the Chinese characters, which is the vertical line on the piedra china, were removed from the tombstone of Donicio Cocqua.

There were other piedra china tiles on the floor of the Binondo Church but all of these were removed when the the church was wrecknovated renovated. The parish priest and the parish council who approved the allowed the destruction of centuries-old of historical artifacts.

Binondo Church is not the only church where the Chinese tombstones were disturbed. Santa Cruz Church, located at the other end of Ongpin Street, has piedra china tiles that are used to fence the plant box.

|

| Piedra china outside of Santa Cruz Church. |

The Chinese characters are clear. Some of the stones bear the text SEPULTURA, which means that they are indeed tombstones.

|

| "SEPULTURA" says the tombstone outside of Santa Cruz Church. |

Santa Cruz Church is currently under the care of the Sacramentinos. However, the church was under the care of the Jesuits, who employed Chinese converts and Tagalogs in building the district of Santa Cruz from marshland into a liveable settlement.

It is sad to note that there is a dearth of study made into the history of the missing piedra china or Chinese tombstones in Binondo and Santa Cruz. This only means that there is much to be uncovered about the history of Manila, which I think will enrich our view of this city and the whole Philippines. Alas! The current state of these valuable artifacts shows that the living Filipinos of today do not care about the lives of the dead Filipinos and the stories that they can tell.

- - -

Read more about Binondo in these blog posts:

1. Visita Iglesia 2019: Our Lady of the Most Holy Rosary Chinese Parish Church (Binondo, Manila)

2. Visita Iglesia: Binondo Church

3. Chinese New Year Feast along Ongpin Street

4. Chinese New Year in Binondo Chinatown

5. A Walk through Quintin Paredes Street

6. A Parade of Delicious Chinese Dishes

7. Yummy Hopia from Salazar Bakery

8. Searching for Wedding Rings and a Bad Day in Binondo Chinatown

9. Lunch Break at Lan Zhou La Mien

- - -

Historical info in this blog post was sourced from the following:

1. The massacre of 1603: Chinese perception of the Spaniards in the Philippines by José Eugenio Borao

2. Chinese mestizo and natives' disputes in Manila and the1812 Constitution: Old privileges and new political realities(1813–15) by Ruth de Llobet

3. Toward a History of Chinese Burial Grounds in Manila during the Spanish Colonial Period by Richard T. Chu and Teresita Ang See